Part one of the improviser’s job. I often think of the improviser’s job as consisting of three different parts, but using those three parts, you then must do a fourth thing, so maybe it’s really four? I’ll let you be the judge.

In my most humble opinion, an individual improviser is simultaneously a writer, an actor, and a director, but they must do all three of those things as a collaborator as well. There are rare examples of one-person improv shows with no collaboration, but even those usually feature a musician or collaboration with the audience, and even the greatest one-person improv will never be as good as the best ensemble pieces, so that’s what I really want to talk about.

Also, I will be looking at this concept from the perspective of comedy. I know improv doesn’t need to be funny to be good, but if we’re being honest, nobody goes to see an improv show expecting high drama outside of experimental theater festivals. We performing improvisers work and perform mostly in comedy theaters, therefore, I will be talking about comedy. But enough with the sidebars!

Let’s get to the first 3 parts of a great improviser: Writer, Actor, Director.

WRITER

I don’t mean writing literally, of course, I just mean that an improviser must choose the words that they speak like a writer must choose the words they put down on the page. Most people who try improv spend quite a lot of time on this aspect, and a lot of them never really get past it. Words are important. Words are useful. We love words. Words! But words aren’t everything.

They can quickly and efficiently establish the base reality of the scene you’re trying to do in an empty black box, providing information such as where we are supposed to imagine the scene taking place and who these people are pretending to be. Humans are capable of miming all of that, but words are faster. The words we choose and the order in which we place them are responsible for the bulk of the raw data required to understand what’s going on in a scene, the basic building blocks in a void to help the audience and fellow improvisers to logically follow the making of pretend. Words are useful.

Words are a big part of Improv 101 or whatever your beginner improv class is called. When we start to learn the basics of how to improvise on stage, most of the “rules” we’re given are about which words to use, and more commonly which words not to use. It’s easy to get fixated on words. It makes sense up to a point. Over the last 75+ years of improvising, common blocks along the road to good scene work have been detected, and “rules” were based on them:

- Yes and…

- Avoid questions.

- Avoid transactions or teaching scenes.

- Don’t go for jokes.

- Tell us where you are.

- Tell us who you are.

- Etc.

All of these little pearls are like bumper lanes at the bowling alley. They can make it a lot easier to find success by avoiding the gutters. They make it easier to avoid cliches, avoid the boring, and get to something interesting and fun a little bit faster so beginners can take advantage of success and see what works. But it’s also pretty easy to feel bogged down by those rules, to feel like you must actively remember them in the course of every show or scene which just puts you in your head and out of the present moment.

Words can be funny too, and we are talking about comedy. I wrote a whole post about it called: (try not to) SAY SOMETHING FUNNY, so I won’t get too into it here, but I can connect the dots: It’s pretty easy to find yourself on the backline trying to think of a funny premise or a succinct line to start the next scene, or interject a funny line into the scene that’s already happening. The problem with that is that you’re too focused on the words in your head instead of the words in the scene, the words that everyone else is paying attention to. It’s easy to miss something. You’re focusing too much on one third of your job (or a quarter) and neglecting the bigger picture. But once you can break the habit of over-thinking the writer role, we come to the actor aspect of the complete improviser.

ACTOR

The role of actor seems obvious, but it usually receives less attention in the beginning than the writer aspect of the improviser’s job. In addition to getting to decide which words we speak, we also get to choose how we say them and where on stage we say them. We get to choose how we present our faces and bodies to the audience, and the way our voices sound (high-pitch, low, accents, etc.). We choose how we interact with other players and objects, real or imagined. Improv is about more than just words.

As an actor in any improv scene, your physicality plays a crucial role in bringing a character to life. Every movement, gesture, and stance communicate something about your character’s personality, mood, and intentions. A simple adjustment in posture can transform you from a timid, insecure person to a confident, authoritative figure. Similarly, your facial expressions are vital in conveying emotions and reactions that words alone might not fully capture. The audience reads your face as much as they listen to your words, and often, it’s the unspoken reaction that gets the biggest laugh or elicits the most empathy.

Vocal choices are another powerful tool in the improviser’s arsenal. How you deliver a line can completely change its meaning and impact. A line delivered in a slow, deliberate tone can create tension or add gravity, while the same line delivered with rapid-fire energy might come off as anxious or comedic. Experimenting with different vocal qualities, such as pitch, volume, and rhythm, can help differentiate characters and add layers to your performance. Accents or vocal quirks, when used judiciously, can further enhance a character and make them more memorable, though they should be applied carefully to avoid slipping into caricature, which I discuss in further detail in the post: Character vs. Caricature in Improv.

Another aspect of the actor role in improv is the way you interact with and react to your fellow performers and the environment. “Acting is reacting” is a common nugget of advice for aspiring actors. Improv, like acting, is inherently collaborative (which I’ll discuss more in a section below), and your actions and reactions on stage are just as important as your dialogue. Being a generous actor means actively listening to your scene partners, responding to their choices, and building on their offers. It also involves being aware of the imaginary space you’re creating together. If someone mimes a door, it’s your job to respect that choice and interact with it as if it were real. Consistency in these physical interactions helps maintain the shared reality of the scene and prevents confusion for the audience.

Objects, whether real or mimed, are another layer of the actor’s responsibility, which I cover in the post, Object Work in Improv, but I’ll sum it up: How you handle a mimed cup of coffee, or a heavy suitcase can add richness to the scene, making it more vivid and believable. The weight, texture, and use of these objects should be consistent and intentional. This attention to detail not only strengthens the scene’s reality but also opens opportunities for humor and character development.

In essence, the actor component of improv is about embodying the scene, not just narrating it. While the words you choose as a writer set the foundation, it’s the actor’s job to bring those words to life in a way that is engaging, dynamic, and true to the character. An effective improviser blends these skills seamlessly, moving beyond just what is said to how it is said, and how it is shown, making the scene resonate on multiple levels. But even with strong writing and acting, a scene or show can be better still with an awareness of direction—a sense of pacing, focus, theme, and purpose—which is where the role of the director comes into play.

DIRECTOR

The director role involves the improviser staying aware of the overall show and its presentation, including aspects like pacing, rhythm, visual presentation, variety, focus, theme, and purpose. This is the most advanced of the three roles and the one that most improvisers begin developing the latest, if they do at all. It’s a level that requires a lot of experience and develops slowly. While it might seem like it adds an extra layer of thinking to an already busy mind, I believe that when refined, it feels more like intuition than conscious thought.

In the director role, an improviser isn’t just concerned with the success of a single scene or character; they’re thinking about the arc of the entire show. This means being mindful of the flow between scenes, ensuring that transitions are smooth, and that the energy remains consistent or changes at just the right moments. For instance, a director-minded improviser will recognize when a high-energy scene needs to be followed by something slower to give the audience—and the performers—a chance to breathe.

The director role also involves being aware of thematic elements and ensuring that the show maintains a cohesive narrative or style. Whether it’s a long-form piece with recurring motifs or a show of short-form games with quick, punchy scenes, the improviser in the director role subtly guides the performance to keep it aligned with its intended tone or message. This might mean nudging the scene toward a particular theme that’s been established earlier or drawing attention to a recurring joke or idea that can be developed further.

Perhaps most importantly, the director role is about making sure that the show serves the audience. It’s easy to get caught up in the moment and forget that the ultimate goal is to entertain. The improviser’s job in the director role maintains a connection to the audience’s experience, sensing when a scene has run its course or when it’s time to shift gears to keep the show engaging. This role requires a deep understanding of pacing—not just within a scene but across the entire performance—and the ability to sense the audience’s energy and respond accordingly. This, alas, is a skill you can only practice in front of an audience, so it can take a while to truly master.

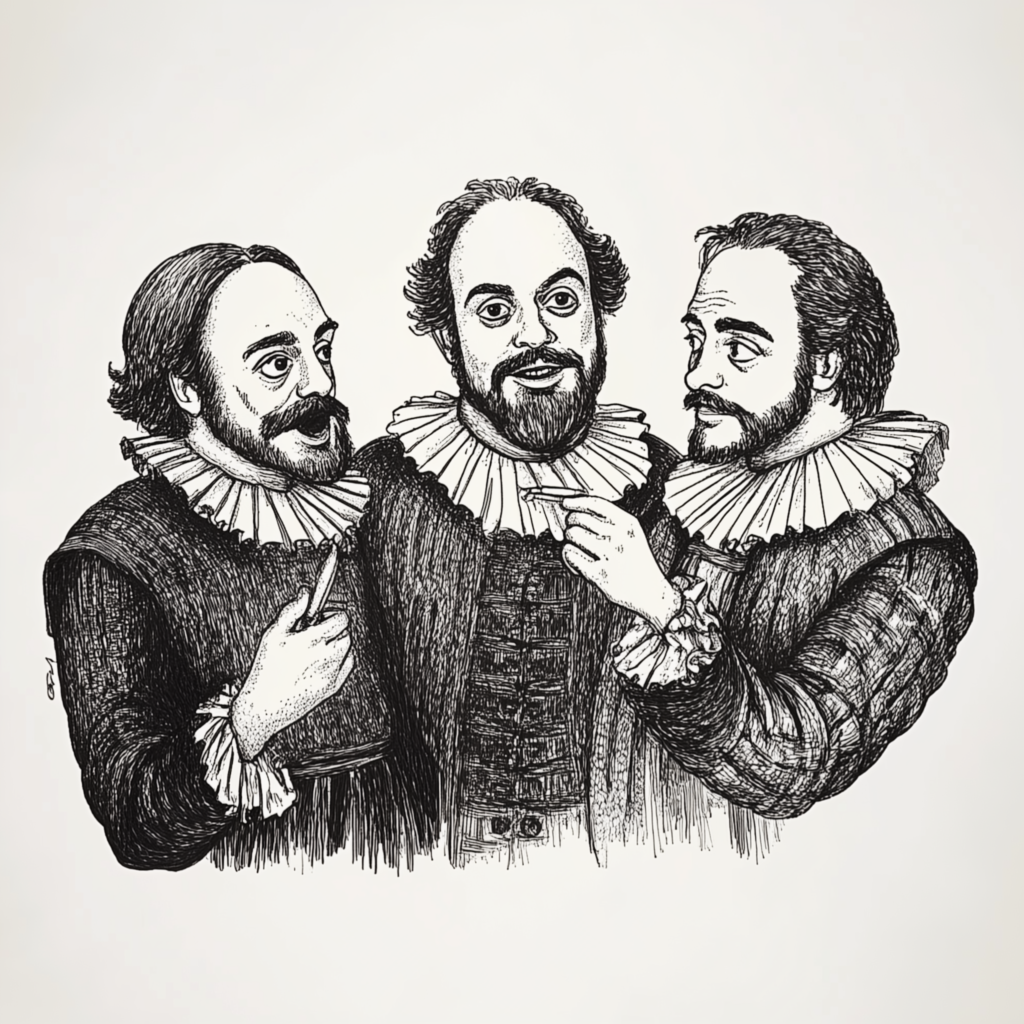

Developing the director aspect of the improviser is a significant achievement, but it still isn’t the whole story. Beyond writing, acting, and directing, there’s one more crucial element that ties everything together: collaboration. Improvisation is, at its heart, a group effort, and no matter how skilled you are in the other roles, your ability to work as a collaborator will ultimately determine the success of any performance.

…and COLLABORATOR (the most important part of the improviser’s job)

And so finally, always remember that collaboration is the cornerstone of improvisation. While the roles of writer, actor, and director focus on individual contributions to a scene or performance, the collaborator role is about how those contributions blend with those of others. Improv is a team activity, where each player supports, enhances, and builds upon the ideas and actions of their fellow performers. No matter how strong your individual skills are, the magic of improv lies in the way you interact with and uplift your scene partners. A good collaborator listens actively, responds with generosity, and remains open to the unexpected turns a scene can take. In the world of improv, collaboration is what transforms a collection of individual talents into a cohesive, entertaining, and memorable show. GROUP MIND IS REAL!!!!

PRACTICE MAKES PERFECT BETTER

Improv is an ongoing practice, like meditation or chess. One should always bring the beginner’s mindset with a sense of openness and play to such creative play. That being said, sometimes it’s hard to schedule time with others for practice, so here are some activities that can help you work on your W.A.D. skills on your own.

IMPROVISER’S JOB AS WRITER

- Write!:

- Timed Free Write: Get a suggestion (from a random word generator or a big hat that you packed with suggestions) and let it inspire a scene that you write. This could be done narratively like a story, or you could write it as dialogue in a script with actions. Time yourself! However long you want. Try to be finished (as in the story has a beginning, middle, and end, before time expires.10 Ways to Say…: Find or invent a line of dialogue that could start a scene, then think of 10 different ways you could get the same ideas out, using different words. Repeat!

- Random Lines: Take a bunch of lines of dialogue (maybe from the previous exercise) and draw two of them from a hat. Use them as the first two lines of dialogue from two characters in a scene, then write the scene, justifying why both lines make sense.

- Timed Monologues: Get a suggestion, then do a character monologue for one minute. Practice identifying the characters base reality and flushing out backstory and major desires or motivators for the character.

- Split Personality Debate: This one is easier with another person to randomize when you switch, but I have done it with an interval timer (for HIIT) and it works. Or you could just look at the seconds on a clock and switch every 10 seconds or whatever, but here is how to play: Start with a topic, it could be anything at all, then start to argue for or against that topic until your timer dings or it’s been 10 seconds, then switch to the opposite perspective. If you were arguing for pineapple on pizza, now you’re arguing against it. Repeat multiple times, switching back and forth.

IMPROVISER’S JOB AS ACTOR

- Mirror Faces: Some people say most of acting is in the face. Take a look at yours. Practice making silly faces and faces that show different emotions and different reactions. Take note of which ones you like and which ones could be better. See if any faces make new voices come out of your mouth or new characters inhabit your body.

- Silly Walks: This can be a workout as well as an acting exercise. Do silly walks that you think are weird. Try walking in as many different ways as you can and think about the types of people (or whatever) might walk that way. This could lead to character monologues too.

- Mime: Practice mime! There are plenty of videos on YouTube if you want tutorials, or you could just practice holding invisible things and touching invisible surfaces. Hold a real thing first, then look at the position your hand is in. Remove the object and hold the same position. Notice the space.

- Voices: There are plenty of YouTube videos that will teach you how to speak in different accents, and those can be fun to practice, but changing your voice can happen in lots of other ways too. Speak high-pitched or low, fast or slow, gruff or whiny. Record yourself and listen back. Explore the boundaries of what your voice is capable of then push those boundaries.

IMPROVISER’S JOB AS DIRECTOR

- Take Notes: Go to shows or watch sketches and literally take notes. Observe the scenes as wholes, but also individual performances. Note what is working and what could make it better.

- Explore Theme: Start with genres you like, and research some of the common tropes and themes that exist within, then move on to other genres. Watch things you like and see if you can identify themes.

- Notice Rhythm: Watch classic comedy sketches or bits in movies and try to observe the rhythm. This can be especially easy with scenes that are set perfectly to music, but I’ve done it with a stopwatch before too. Notice the spaces in-between the funny bits, the pauses and rests. Notice the build and release. Pick one thing you love and dissect it, time-stamping everything to see it skeleton.

- Experience Art: Seriously. As much variety as possible. The best improvisers have the deepest wells of inspiration, so go out and get some. Branch out. Try new things. See how other arts could impact your own. Enrich your life, enrich your improv.